Memory, History, and My Windows in Berlin

When I lived in Berlin between 1989 and 2005, my home stood at two very symbolic addresses. First, for two years, I lived on Leipziger Strasse, just a short walk from Checkpoint Charlie, where the Wall still cast its long shadow over daily life. From 1991 to 2005, I moved to Wilhelmstrasse, near the Brandenburg Gate — a place where the city’s fractured past and its attempts at renewal could be seen and felt every day.

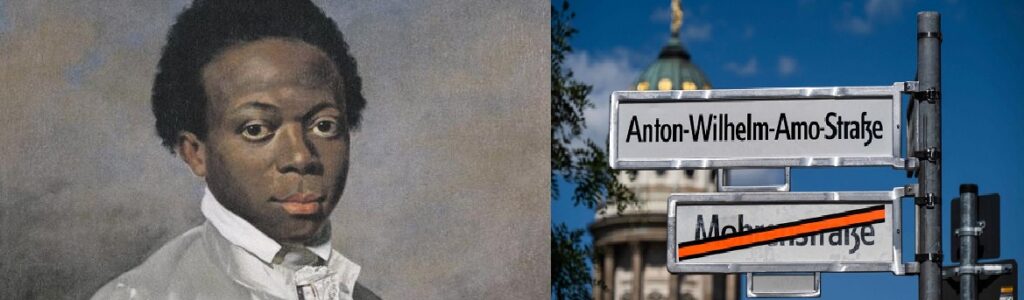

From one side of the flat, I looked directly onto Wilhelmstrasse, a street once dominated by Hitler’s Reich Chancellery, a reminder of dictatorship and destruction. From the other side, my windows opened onto Mohrenstrasse, which had only just been renamed in August 2025 as Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Strasse, and Zietenplatz.

The view was heavy with history. Zietenplatz was flanked by bronze equestrian statues of four Prussian generals: Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin, Hans Karl von Winterfeldt, James Francis Edward Keith, and Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz. Their presence was part of a broader ensemble commemorating the military traditions of the 18th century, which also included Hans Joachim von Zieten and Leopold I of Anhalt-Dessau, the “Old Dessauer,” whose monuments stood nearby at Wilhelmplatz. These figures were celebrated as heroes of Frederick the Great’s wars — embodiments of Prussia’s rise as a military power. Yet in their stern faces and martial poses, I often sensed more of the weight of a militaristic past than any sense of civic pride.

For me, however, the statues were less important than the street name. “Mohrenstrasse” — literally “Street of the Moors” — had long been criticised for its racist overtones. I remember the unease of walking past the U-Bahn sign day after day, aware of how words can wound and perpetuate a history of exclusion. Through my windows, I could see both the shadows of imperial Prussia and the scars left by dictatorship, but what I could not yet see was how Berlin would begin to reckon with that legacy.

That reckoning has finally come with the decision to rename the street after Anton Wilhelm Amo.

Born in what is now Ghana around 1703, Amo was brought to Europe as a child and became the first African to study and teach at German universities.

A philosopher and legal scholar, he studied philosophy, medicine, and law, earning degrees in Halle and Wittenberg before going on to lecture in Jena.

He was fluent in German, Dutch, Latin, Greek, and French, and his writings reveal both erudition and an independent voice. Among his best-known works are De Humanae Mentis Apatheia (On the Impassivity of the Human Mind, 1734) and Tractatus de Arte Sobrie et Accurate Philosophandi (Treatise on the Art of Sober and Careful Philosophising, 1738), in which he explored questions of mind and body, freedom, and rationality.

Despite his brilliance, he faced racial prejudice throughout his life and eventually returned to West Africa, where he died in relative obscurity. Naming a street after him restores his memory to the city and honours an intellectual legacy that was long ignored.

For me, the change is more than a gesture. It is a way of saying that Berlin — and by extension, Europe — belongs to all who have lived, thought, and struggled within it. Amo’s name on the map stands for dignity, resilience, and the possibility of a more inclusive story.

I feel deeply connected to this shift. Having lived with these names, with these views, I see how profoundly symbols shape our sense of belonging. To rename a place is not to erase history but to rebalance it, to invite a more honest conversation about who we were and who we aspire to be.

Berlin taught me that memory is always contested ground. I lived between Wilhelmstrasse, haunted by dictatorship, and Mohrenstrasse, branded with colonial language. Today, Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Strasse speaks of another possibility: that we can choose diversity over exclusion, equality over hierarchy, respect over racism.

The view from those windows is long gone, but the conviction remains: our cities should tell stories that include us all.