Textures, Traditions and Signature Dishes

When people think of Vietnam’s food culture, the first image that often comes to mind is a steaming bowl of phở. Yet this is just the beginning of a much larger story. Across the country, noodles are not merely an ingredient but a culinary language—one that speaks of geography, history, migration, and daily life.

Just as Italy transformed wheat into countless forms of pasta—spaghetti, fettuccine, gnocchi, macaroni—Vietnam has taken rice, wheat and starches such as tapioca or mung bean and created its own astonishing variety of noodles. Each type has a distinct texture and is paired with dishes that are inseparable from local identity. A bowl of bún bò Huế tells of central Vietnam’s bold, spicy palate, while cao lầu whispers the history of Hội An’s trading port. Even the same noodle can carry different meanings from north to south, with broth styles, garnishes and side herbs changing dramatically along the way.

Eating noodles in Vietnam is therefore not simply about satisfying hunger. It is about experiencing the rhythms of everyday life: the dawn bowl of phở on a street corner, the lunchtime bún chả with colleagues, the late-night hủ tiếu stall where conversation flows as freely as the broth. To know the noodles is to know the country itself.

What follows is a guide to the principal types of Vietnamese noodles—how they are made, what they taste like, and the signature dishes that showcase them best.

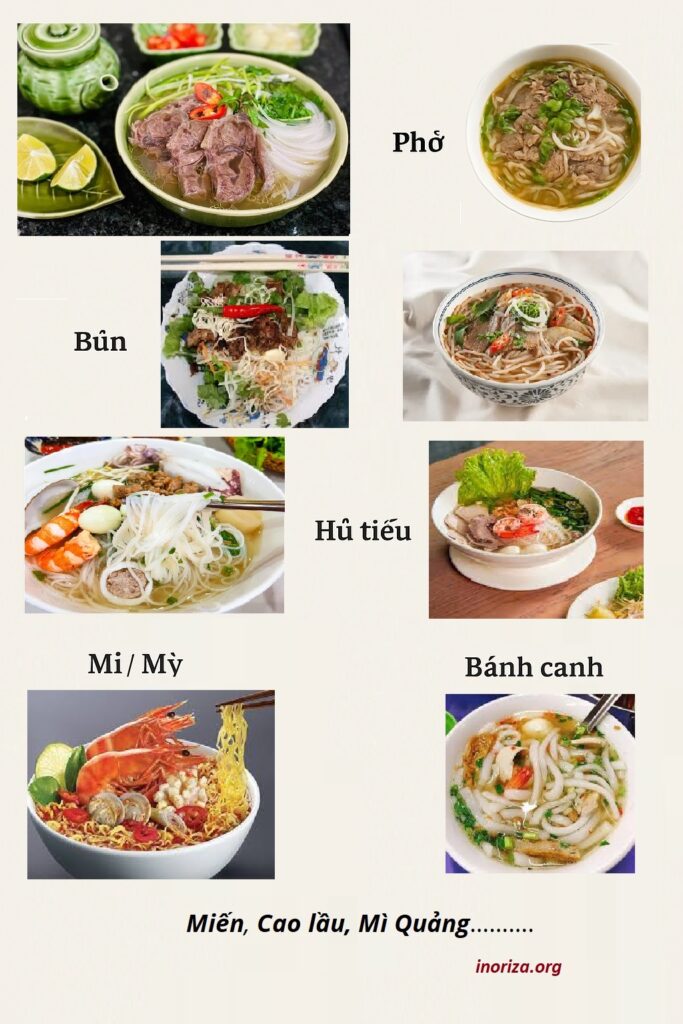

1. Phở (Flat Rice Noodles)

The most internationally famous Vietnamese noodle, phở is made from rice flour pressed into wide, flat sheets and cut into ribbons. Soft, silky and slightly slippery, these noodles are inseparable from the iconic phở broth.

The broth itself is a masterpiece of patience: simmered for hours with beef bones or chicken, infused with spices such as star anise, cinnamon and cloves. Northern styles are clear, elegant and restrained, while southern bowls are often sweeter, more herb-laden, and accompanied by bean sprouts, lime and chilli.

Signature dishes: Phở bò (beef phở) and phở gà (chicken phở). Beyond the dish, phở carries symbolism: born in Hanoi in the early 20th century, it has become a national emblem and a morning ritual across Vietnam.

2. Bún (Rice Vermicelli)

Bún are thin, round rice noodles with a springy softness. Unlike phở, they are not flat but thread-like, and they appear across Vietnam in countless variations.

They are remarkably versatile: used cold in fresh salads, grilled meat dishes, or dunked into rich broths. In Hanoi, bún chả (grilled pork with vermicelli and herbs) became world-famous after Barack Obama and Anthony Bourdain shared a meal together in 2016. In Huế, central Vietnam, the same noodle appears in bún bò Huế, a fiery beef and lemongrass soup with thicker, rounder strands.

Signature dishes: Bún chả, bún thịt nướng, bún bò Huế. More than just noodles, bún represent the adaptability of Vietnamese cuisine—from light, refreshing fare to bold, spicy meals.

3. Hủ Tiếu (Clear Rice Noodles)

Distinct from phở and bún, hủ tiếu noodles are slightly translucent, often made with a mix of rice and tapioca flour, giving them a chewy, elastic bite.

Originating in southern Vietnam with influences from Cambodian and Chinese communities, hủ tiếu is a true melting-pot dish. Its broth is typically lighter and sweeter than phở, and it can be enjoyed in two ways: in soup (hủ tiếu nước) or “dry” with a separate dipping sauce (hủ tiếu khô).

The most celebrated version is hủ tiếu Nam Vang, named after Phnom Penh (“Nam Vang” in Vietnamese), reflecting the Cambodian origins of the style.

Signature dishes: Hủ tiếu Nam Vang, hủ tiếu Mỹ Tho. Often eaten late at night or as a hearty breakfast, it symbolises the cosmopolitan spirit of the Mekong Delta.

4. Mì / Mỳ (Egg or Wheat Noodles)

Borrowed from China but wholly naturalised in Vietnam, mì (or mỳ) are yellow, springy noodles made with wheat flour and sometimes eggs. Their firmer texture sets them apart from the softer rice noodles.

They are a mainstay in soups like mì hoành thánh (wonton noodle soup) or stir-fried dishes (mì xào), where their chewiness pairs beautifully with vegetables, seafood and soy-based sauces. In Vietnam, mì stalls often cater to late-night diners, offering comfort and energy for the hours ahead.

Signature dishes: Mì hoành thánh, mì xào giòn (crispy fried noodles).

5. Miến (Glass Noodles)

Made from mung bean or arrowroot starch, miến are translucent, slippery noodles often called “glass noodles.” Their lightness makes them ideal for soups or fillings.

One of the most beloved dishes is miến gà, a clear chicken soup often eaten during Tết (Lunar New Year) as a lighter alternative to heavier rice cakes. Miến also appear wrapped in spring rolls, where their texture adds subtle chewiness.

Signature dishes: Miến gà, miến lươn (eel glass noodle soup). These noodles carry an air of refinement and celebration.

6. Bánh Canh (Thick Noodles)

Hearty and rustic, bánh canh noodles are thick, chewy strands made from tapioca or a rice–tapioca blend. Their texture resembles Japanese udon but with more elasticity.

They are commonly served in robust, slightly viscous broths that cling to the noodles, often featuring crab (bánh canh cua), pork hock or shrimp. In many southern households, bánh canh is a weekend comfort food—slowly simmered, family-style, and meant to be shared.

Signature dishes: Bánh canh cua, bánh canh giò heo tôm.

7. Cao Lầu

A noodle found only in Hội An, cao lầu is steeped in legend. The thick, yellow noodles resemble Japanese udon but have a firmer bite. According to tradition, they must be made using water drawn from a specific ancient well in Hội An, lending them their unique texture.

The dish itself combines noodles with slices of pork, fresh herbs, bean sprouts and crispy rice crackers, served with just a splash of broth. Its origins are thought to reflect Hội An’s past as a trading port, where Chinese, Japanese and Portuguese influences mingled.

Signature dish: Cao lầu. Eating it in Hội An is considered an essential culinary pilgrimage.

8. Mì Quảng

Hailing from Quảng Nam province in central Vietnam, mì Quảng features wide, turmeric-tinted rice noodles with a vibrant yellow hue. Unlike phở or bún, mì Quảng is not a soup but rather a noodle dish served with a modest amount of intensely flavoured broth.

It is topped with pork, shrimp, fresh herbs, roasted peanuts, and crispy sesame crackers, creating a colourful, textured bowl that epitomises the bold spirit of central Vietnamese cuisine.

Signature dish: Mì Quảng. Known for its festive appearance, it is often associated with family gatherings and celebrations.

Conclusion

From the elegant phở of Hanoi to the golden mì Quảng of central Vietnam and the cosmopolitan hủ tiếu of the south, noodles form the backbone of Vietnam’s culinary map. Each bowl tells a story: of migration, of adaptation, of local pride.

Italy may have its pasta, but Vietnam has something just as rich: a true noodle multiverse, where every strand connects food to culture, history and identity.