New Breakdown of International Law? Failure of Diplomacy?

25 July 2025

Abstract: This analysis examines the protracted border conflict between Thailand and Cambodia, centred on the sovereignty of the Preah Vihear Temple and adjacent territories. While rooted in colonial-era demarcation disputes and the 1962 International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling affirming Cambodia’s title to the temple, the contemporary crisis has been critically reignited and exacerbated by Thailand’s internal political instability since 2006. Escalating military engagements—including aerial assaults, artillery exchanges, and alleged landmine deployment—since 2008 have resulted in significant casualties, displaced civilians, and raised profound questions concerning compliance with international humanitarian law and the UN Charter’s prohibition on the use of force.

The conflict’s regional repercussions are substantial, threatening economic stability through disrupted supply chains, suspended cross-border trade, diminished tourism, and potential labour market dislocations affecting millions of Cambodian migrant workers in Thailand. Diplomatic mechanisms, notably the ASEAN-facilitated Joint Border Commission (JBC), have thus far failed to contain hostilities, revealing limitations in regional conflict-resolution frameworks. Nevertheless, pathways to de-escalation exist. Historical precedent demonstrates bilateral reconciliation is achievable through negotiation, supported by ASEAN’s convening role and offers of third-party mediation (e.g., Malaysia, Indonesia). Concrete measures—such as phased troop withdrawals, neutral observer deployments, collaborative demining, and ICJ adjudication—could facilitate a return to dialogue.

Ultimately, the crisis underscores the vulnerability of Southeast Asia to latent territorial disputes but also presents an opportunity to reinforce multilateral institutions. A peaceful resolution hinges on political will within Thailand and Cambodia, calibrated external pressure, and the revitalisation of diplomatic norms, affirming that adherence to international law and sustained dialogue remain the only sustainable foundations for regional stability.

1. Introduction

One of the most pressing issues in Southeast Asia in early 2011, in addition to Thailand’s ongoing political crisis, has been the border conflict in the country’s northeast with Cambodia. This dispute is closely linked with Thailand’s internal political turmoil and has made the region the most dangerous conflict zone at the present time. Although the border conflict is already more than a century old, tensions have intensified sharply since 2008, coinciding with an escalation of Thailand’s political crisis and the consequent political weakness of the Thai government.

The conflict centres on the border demarcation around the 11th-century Preah Vihear Temple, built by the Khmer Empire, and the surrounding area, which Thailand claims as its own (though Cambodia also asserts sovereignty). While the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled in 1962 that the temple itself lies in Cambodian territory, it remains unclear – at least from Thailand’s perspective – whether the land around the temple belongs to Cambodia or to Thailand.

2. Origin of the Problem

Historical Context: Tensions between Thailand (Siam) and Cambodia are deeply rooted in centuries of shared history and border conflicts. As early as the fifteenth century, Siamese forces seized control of Angkor, toppling the capital of the Khmer Empire in 1431. Territorial wars persisted throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; for instance, the Thai conquest of the Cambodian capital, Longvek in 1594 dealt a severe blow to Khmer sovereignty. Several historical disputes have profoundly shaped the collective memory of both nations.

The dispute between Cambodia and Thailand over control of the Preah Vihear Temple (11th–12th centuries) remains emblematic. and dates back to a 1904 treaty between French Indochina (which then ruled Cambodia) and the Kingdom of Siam (now Thailand). That treaty provided for the border to be defined by a joint Franco-Thai commission. Over the years following 1904, this mixed commission studied the area around Preah Vihear Temple and concluded that the temple lay within what is today Cambodia. This conclusion was ratified on 23 March 1907 by a new border agreement between the two sides. Crucially, Thailand, in subsequent years and in later treaties with French Indochina (1925, 1937 and 1947), accepted the commission’s findings and never formally repudiated that agreement.

Although it seemed the dispute had been settled, Thailand sent troops to occupy Preah Vihear in 1954. In response, Cambodia, to resolve the Preah Vihear issue that had arisen with the Thai occupation, asked the ICJ on 6 October 1959 to give a final decision on the status of the temple and thus end the controversy between the two countries.

On 15 June 1962, the ICJ delivered a historic judgment containing two critical components for future developments. First, by a vote of 9–3, the Court held that “[t]he Temple of Preah Vihear was situated in territory under the sovereignty of Cambodia and, in consequence, that Thailand was under an obligation to withdraw any military or police forces, or other guards or keepers, stationed by her at the Temple, or in its vicinity on Cambodian territory.” (ICJ, 1962). Accordingly, the Court confirmed that the temple itself was on Cambodian territory and required the removal of all Thai military forces from the area.

The second important finding, by a vote of 7–5, was that “Thailand was under an obligation to restore to Cambodia any sculptures, stelae, fragments of monuments, sandstone model and ancient pottery which might, since the date of the occupation of the Temple by Thailand in 1954, have been removed from the Temple or the Temple area by the Thai authorities.” (ICJ, 1962). In other words, Thailand was obliged to make good any damage or removals caused by its occupation forces. Thus, the ICJ’s decision definitively established that Preah Vihear Temple lies in Cambodia and, at the same time, demanded action to address any harm done to the temple by Thailand. Following Cambodia’s request, this judgment was intended to close the dispute between the two countries – a goal that was achieved until 2008, when the issue re-emerged with renewed intensity driven by Thailand’s internal political crisis.

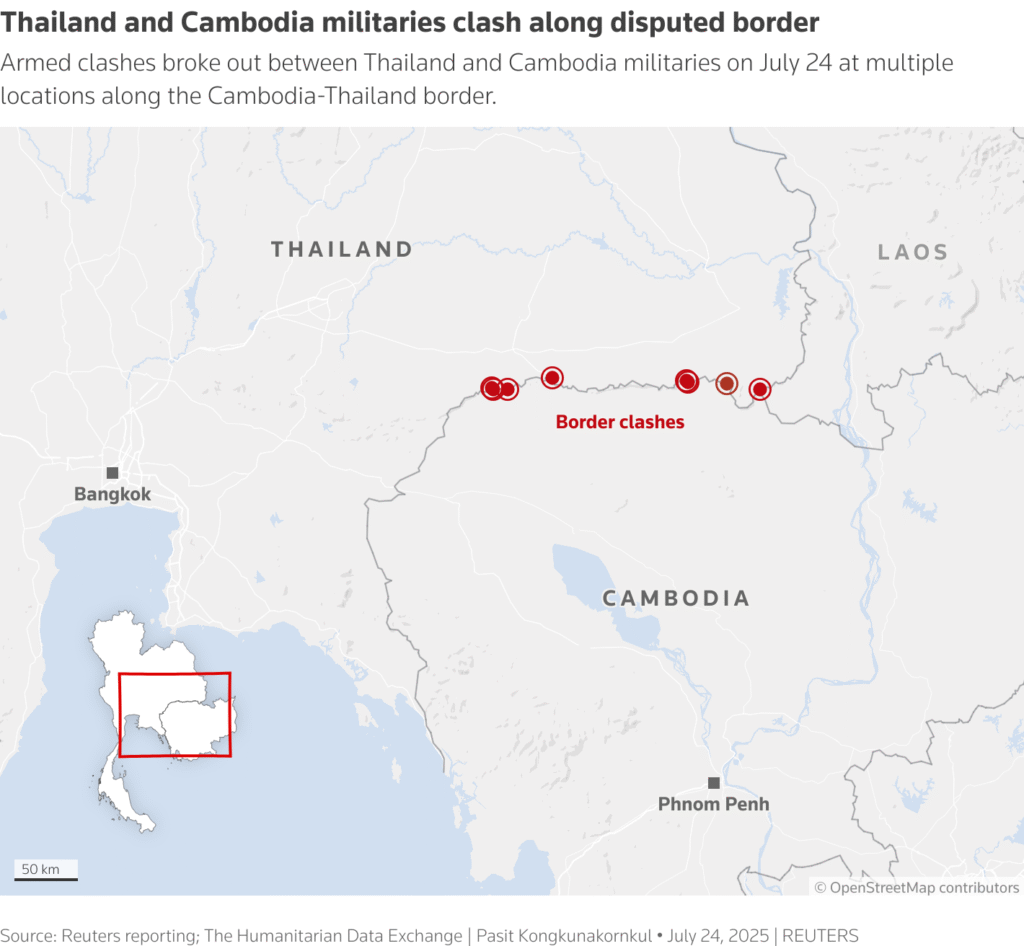

3. Map of the Disputed Border Area

4. Political Crisis in Thailand and Its Relation to the Outbreak of the Conflict

Thailand has been mired in a serious political crisis since a military coup in 2006. While Thailand’s legitimately elected prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, was abroad on official travel, the army – with support from both the monarchy and opposition politicians – overthrew his government. Since that coup, a series of events has shaped Thailand’s political trajectory and, consequently, the conflict over the Preah Vihear Temple.

The first such event was the 2007 parliamentary elections, held to restore a semblance of democracy after the coup. These elections, heralded as the political solution to the previous upheaval, actually brought no improvement: the results led once again to a victory by a party aligned with Thaksin Shinawatra, the People’s Power Party (PPP)*. The PPP candidate Samak Sundaravej became prime minister, but he served only a few months before being forced to resign. The Thai Constitutional Court ruled that he had violated the constitution by appearing on a cooking show, which made him ineligible to hold office. The second event was that his successor, Somchai Wongsawat (also of the PPP), similarly lasted only briefly. Somchai was accused of electoral fraud and corruption by the Constitutional Court and was compelled to resign as well.

After this double ousting, Abhisit Vejjajiva emerged as the acting prime minister. He was selected by a Parliament in which many members of the PPP and of its allied minor parties had been expelled amid allegations of electoral fraud and other offenses. Abhisit Vejjajiva thus became Thailand’s prime minister in 2008. Since then, political instability and tension have remained pronounced. This ongoing volatility stems from several factors: the profound weakness of all political parties, widespread corruption pervading the political system, and the limited development of democratic norms in Thailand. These conditions mean that electoral victories are often contested through legal challenges or public street protests rather than being accepted as legitimate.

It was during the final government of Thaksin Shinawatra’s allies (i.e., in 2008, just before Abhisit Vejjajiva took office) that the Preah Vihear conflict erupted between the two countries. When UNESCO declared the temple a World Heritage Site – thus formally recognising it as on Cambodian territory – the Thai opposition lashed out at the national government. Opposition figures accused the government of being complicit with Cambodian interests, of betraying national interests, and even of being a “sellout” to Cambodia. In this way, the resurgence of the Preah Vihear conflict was directly tied to Thailand’s domestic political crisis and its internal power struggles. Thailand’s opposition used the Preah Vihear case to weaken Thaksin’s faction by arguing that the national interest was at risk.

However, Abhisit Vejjajiva’s ascent to power only intensified the conflict between the two countries. This was especially so with the renewed involvement of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who was appointed as an economic adviser to Cambodia’s leader. In Thailand, this appointment was seen as a provocation by the former prime minister. From UNESCO’s declaration on 8 July 2008 to the present day, there have been numerous military skirmishes between the armies of the two countries, resulting in multiple fatalities and making this the main interstate armed conflict in Southeast Asia. The situation reached a climax in February 2011 when a Cambodian court convicted two Thai ultranationalists – who had illegally crossed the border – of espionage, sentencing them to eight years in prison.

5. Chronology of the Conflict: July 2008–Present

The re-emergence of the conflict between Thailand and Cambodia over Preah Vihear’s sovereignty has been marked by dozens of armed skirmishes between the two countries’ armed forces. These clashes have resulted in the deaths of several dozen soldiers and the displacement of thousands of civilians in the border region.

• 15 July 2008: Three Thai citizens are arrested for illegally accessing the temple area.

• 3 August 2008: First exchange of gunfire between Cambodian and Thai soldiers. No casualties reported.

• 6 October 2008: Two Thai soldiers are injured by a landmine.

• 15 October 2008: First fatalities of the conflict occur during a second armed exchange. Three Cambodian soldiers and one Thai soldier are killed.

• 3 April 2009: Third armed clash. Two Cambodian soldiers and one Thai soldier killed.

• 19 September 2009: First clash on Thai soil, between Thai ultranationalist protesters and Thai security forces.

• 28 September 2009: Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen orders his forces to shoot anyone illegally crossing the border.

• 24 June 2010: Renewed exchange of fire between the two armies.

• 8 August 2010: The Cambodian president formally complains to the United Nations about Thailand’s threat of force.

• 1 February 2011: A Cambodian court sentences two Thai citizens to eight years in prison for illegal entry and espionage.

• 4–7 February 2011: Six people are killed in exchanges of artillery fire between the armies.

• 9 February 2011: Cambodian President Hun Sen declares that Thailand has effectively declared war on Cambodia.

• 15 February 2011: New shooting incidents between the two armies. ASEAN intervenes in response to the escalation and decides to send 40 Indonesian civilian and military observers to the area shortly to verify the situation and seek a peaceful resolution (ASEAN, n.d.).

• 22 April – 3 May 2011: New clashes result in the highest number of casualties, with nine Thai and seven Cambodian soldiers killed.

• 2 May 2011: Facing a worsening situation, the Cambodian government asks the ICJ to clarify its 1962 judgment to help defuse the conflict.

• 4 May 2011: Both sides sign a ceasefire that remains in effect to date.

• 11 November 2013: ICJ reaffirms Cambodia’s sovereignty over Preah Vihear vicinity, orders Thai withdrawal.

• February 2025: Cambodian troops perform national anthem at Ta Moan Thom, provoking a diplomatic crisis

.• 24 July 2025: Unprecedented aerial escalation: F-16 fighter jets deployed in direct combat operations.

6. Mutual accusations

Thailand has accused Cambodia of planting anti-personnel landmines in the disputed border area, wounding its troops. Bangkok’s military reported finding fresh Russian PMN-2 mines (not used by the Thai army) near patrol routes, and said multiple soldiers had been injured by them – one lost a foot and another lost a limb. Thai officials also claim Cambodian artillery shelled at least three Thai border villages (killing civilians, including a young girl) and that movements of Cambodian troops and a band singing the Cambodian anthem at Ta Moan Thom temple were deliberate provocations.

Phnom Penh flatly denies laying new mines, saying any explosions stem from leftover ordnance, and in turn accuses Thailand of military aggression. Cambodia condemned a recent Thai air strike as “reckless and brutal military aggression” and defended its right to counter what it calls an unprovoked invasion. Prime Minister Hun Manet warned that, despite a preference for peaceful solutions, Cambodia’s forces would “respond with force” to defend sovereignty. In a letter to the UN Security Council, Phnom Penh formally requested a meeting to address what it called Thailand’s “unprovoked and premeditated” aggression.

In summary, both sides accuse the other of violating territorial integrity and endangering civilians – a cycle of mutual recriminations that has stalled dialogue. Cambodia has appealed to the UN for intervention, while Thailand insists on handling the dispute bilaterally through existing channels such as the Joint Boundary Commission, treating the incident as a national security issue.

7. Previous partial solutions and proposed mediation

Since 2000 Thailand and Cambodia have had a Joint Border Commission (JBC) to peacefully manage their territorial claims, but it has produced scant results. Talks scheduled for 14 June 2025 – at which both sides had hoped to ease tensions – were overtaken by renewed clashes.

After the last flare-up in 2008–2011 the neighbours had observed a fragile ceasefire: mixed Thai–Cambodian patrols (sometimes with neutral UN/ASEAN observers around Preah Vihear) helped keep a lid on fighting, but the underlying dispute remained unresolved.

Regional powers have urged de-escalation and dialogue. Malaysia – the current ASEAN chair – publicly called on both sides to “stand down” and resume talks, stressing the need for a ceasefire. Vietnam’s foreign ministry likewise appealed for the conflict to be settled through diplomacy “in accordance with … ASEAN’s spirit of solidarity”.

The Philippines urged a peaceful settlement under international law and encouraged maintaining “open lines of communication” to de-escalate. Other ASEAN states (Indonesia, Laos, etc.) could offer quiet facilitation, although no formal trilateral talks have been reported.

China has offered to play a constructive role by upholding an “objective and fair” position and helping both sides resolve the dispute through friendly dialogue.

Powers like Japan, the EU or the United States might also pressure Bangkok and Phnom Penh diplomatically to engage. In practice, a mix of “carrot-and-stick” measures has been discussed.

Thailand has already closed certain border crossings (e.g. Ban Mueang Dan and Phra Viharn) and suspended some trade agreements to pressure Cambodia. These sanctions are intended to push for talks.

At the same time, shared incentives like joint humanitarian aid or third-party mediation could entice cooperation. Experts have proposed confidence-building steps such as establishing a direct military hotline to avoid misunderstandings, gradually pulling troops back to reserve positions, and deploying international observers (e.g. UN or ASEAN monitors) in the contact zones. Some have even suggested a coordinated effort to clear old landmines safely.

None of these have been implemented yet, but they form the basis for potential ceasefire and monitoring arrangements. The role of multilateral organisations is crucial but sensitive. ASEAN is officially committed to regional peace, but its non-interference policy has so far limited intervention.

Nevertheless, Malaysia’s prompt statements show the bloc can exert political influence. Invoking the ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) – which obliges members to settle disputes peacefully – could formalise the pressure to de-escalate.

At the UN level, the Security Council could theoretically demand a ceasefire, though great-power interests and regional preferences for bilateral solutions may complicate that. By late July the international community was indeed watching closely: China, Malaysia and Vietnam had all urged restraint and dialogue on 24 July.

8. Economic and social impact

Trade: In 2024 overland trade between Thailand and Cambodia was valued at roughly 175.5 billion baht (about US$5.3 billion). Key Thai exports include beverages, auto and motorcycle parts, engines and agricultural machinery, while Cambodia sends mainly cassava (tapioca), scrap metals (aluminium and copper) and electrical cables. These goods pass daily through at least 18 official border checkpoints. The Thai government has temporarily closed some of the busiest crossings (notably Ban Mueang Dan and Phra Viharn). If these closures were extended or made more widespread, up to about 95% of bilateral border trade could be suspended. Analysts estimate that a full border closure might cost Thailand on the order of 10 billion baht per month. This would not only strip away tens of billions in annual commerce but also affect Thai industries relying on Cambodian inputs.

Tourism: The fighting has hit border tourism hard. In Thailand’s northeast, many small provincial hotels depend on cross-border visitors. Before the latest clashes, hotel occupancy in the lower Northeast was already only about 40% (due to seasonal factors). Owners warn that continued fighting will drive more tourists away. Several eco-tourism sites in Thailand’s border provinces, and even Cambodian temples in contested zones, have closed temporarily for safety. If the conflict lingers, tourism businesses – mostly medium-sized and domestic-market oriented – fear layoffs and bankruptcies. Major centres like Bangkok or Phuket see little direct effect yet, but the overall chill could deter investors and visitors in affected areas.

Labour and migration: Millions of Cambodian workers live in Thailand, a significant portion of its labour force. Official figures cite 1.2 million Cambodians in Thailand (with perhaps over 2 million when undocumented workers are counted). They are concentrated in agriculture, construction and services. For example, more than 80% of the agricultural workforce in Chanthaburi province are Cambodian migrants. A sudden cutoff of this labour supply would be devastating: Thai farmers could be unable to harvest their crops, and agro-industries (which rely on Cambodian-produced materials like animal feed and packaging) would also suffer.

Even healthcare is affected: many Cambodians cross into Thailand for medical treatment, so border closures risk collapsing this cross-border care system. In anticipation, Cambodian authorities and banks have begun preparing.

Following PM Hun Manet’s appeals, Cambodian banks and microfinance firms have agreed to let returning migrant workers pause or extend loan repayments in order to ease their financial burden. In sum, while a massive migrant “return” crisis has not yet unfolded, Cambodia is taking steps (like flexible debt arrangements) to mitigate the impact if Thai workers suddenly come home.

9. A New Breach of International Law? Diplomatic Failure?

The use of force by two ASEAN members challenges international legal norms. The UN Charter prohibits force except in self-defence or under Security Council authorisation. Neither party has formally invoked Article 51 (self-defence), and the confrontation’s scale—aerial assaults and civilian casualties—far exceeds minor border incidents. Should evidence confirm Thai units initiated fire or crossed the border (as Cambodia asserts), Thailand would have violated Cambodian sovereignty. Conversely, deploying mines in contested territory raises legal ambiguities. Thailand’s government cites legitimate defence (“responding to Cambodian fire”), yet the lethality of its airstrike (F-16 deploying ordnance) elevates this to inter-state armed conflict, triggering international humanitarian law obligations. Civilian infrastructure—including a hospital in Surin struck by artillery—and populations have been affected (reuters.com). Indiscriminate mine deployment further breaches humanitarian norms.

Cambodia emphasises Thailand’s duty of non-aggression, denouncing the airstrike as territorial violation and invoking peaceful dispute resolution principles enshrined in regional treaties.

Diplomatic channels have thus far proved ineffective. Established mechanisms (the Joint Border Commission, bilateral talks) failed to prevent escalation and appear exhausted. Both capitals exchanged formal notes demanding troop withdrawals without tangible agreements. Domestic criticism has emerged: Thailand’s interim Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra emphasised peaceful resolution as her priority, though political divisions (her family’s ties to Hun Sen versus nationalist military factions) complicate consensus. Cambodia’s recourse to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) demonstrates eroded bilateral trust. This episode reveals a profound diplomatic rupture, as pacific settlement norms have been disregarded. Analysts contend the confrontation undermines regional diplomatic protocols; indeed, some argue diplomacy has been “sidelined” by nationalist belligerence.

Nevertheless, systemic collapse is not inevitable. External actors’ swift condemnation of violence and institutional appeals (UN, ICJ) affirm extant pathways to dialogue. This crisis may necessitate reinterpreting regional security norms: a putative “new breach” of international law could be remedied by reinforcing those very norms, bolstering pacific arbitration, and implementing mutually committed dispute-resolution mechanisms.

10. Prospects for Mediation and Dialogue

Despite grave circumstances, cautious optimism regarding dialogue resumption is warranted. Thailand and Cambodia are proximate neighbours with deep cultural and economic ties; past crises (e.g., 2003 embassy closures) were invariably resolved through negotiation. Both governments publicly prioritise peace: Thailand’s Prime Minister reiterated commitment to resolving border disputes “peacefully”, while Cambodia espouses pacific methods (while defending sovereignty).

An institutional framework remains available. The Joint Border Commission (JBC), though currently ineffective, could be revitalised with international support (e.g., under ASEAN oversight). Precedent suggests negotiating a ceasefire protocol monitored by neutral observers (e.g., Red Cross or UN personnel) to oversee troop withdrawals. Concurrently, mediation offers from Malaysia (ASEAN chair), disinterested parties (Indonesia, Singapore), or global actors (EU, Japan) could provide impartial oversight. A tangible roadmap might entail:

• Phased de-escalation: Mutual frontline withdrawal and collaborative demining.

• High-level demarcation talks: Facilitated by ASEAN.

• ICJ involvement: Adjudicating evidence if Thailand reconsidered jurisdiction (Cambodia has filed a formal request, reuters.com).

• Third-party pressure: The U.S. and China jointly urging acceptance of “peace observer” missions.

Tension reduction offers mutual benefits: restoring trade (averting projected multimillion-pound losses, nationthailand.com), reviving tourism, and safeguarding migrant employment—vital for both economies. Economic analysts note that reopening border checkpoints after prior crises precipitated rapid trade recovery. Furthermore, reallocating economic commitments (e.g., joint infrastructure or energy projects) could enhance mutual trust.

In conclusion, though this represents the gravest bilateral friction in 13 years, pathways to reconciliation exist. History demonstrates animosities can be set aside when governments choose negotiation. With calibrated pressure from mediators (ASEAN and sympathetic powers) and political will from both nations, a return to pacific diplomacy remains feasible. Peaceful resolution would avert immediate humanitarian and economic catastrophe while reinforcing international institutions’ legitimacy. Thus, this conflict could fortify regional dialogue culture, strengthen multilateral mechanisms (ICJ, ASEAN, UN), and underscore that law and diplomacy constitute the sole sustainable long-term trajectory.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, 24 July). Thailand–Cambodia updates: Over 10 killed in clashes at disputed border.

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Anheier, H. K. (2007). Conflicts and tensions. Sage.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2021). ASEAN Charter. https://asean.org/asean/asean-charter/

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). (n.d.). ASEAN website. Retrieved from http://www.asean.org

Bangkok Post. (2025, 22 July). Thailand warns Cambodia after border skirmish.

Bangkok Post. (2025, 23 July). Thaksin accuses Hun Sen of ordering first strike.

Bangkok Post. (2025, 23 July). Cambodia ‘laying mines’.

Bangkok Post. (2025, 23 July). Thailand recalls ambassador from Cambodia amid border tensions. Bangkok Post. Bangkok Post. (2025, 24 July). Thailand launches airstrike on Cambodia as border clash escalates.

Bangkok Post. (2025, 23 July). Tourism seen taking a hit if border conflict persists.

BBC News. (2024, July 23). Cambodia and Thailand trade accusations over border military build-up.

Bercovitch, J. (2011). Unraveling internal conflicts in East Asia and the Pacific: Incidence, consequences and resolutions. Lexington Books.

Bizot, F. (2001). The Gate. Alfred A. Knopf.

Chachavalpongpun, P. (2013). Reinventing Thailand: Thaksin and His Foreign Policy. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Council on Foreign Relations. (2024, July 21). Southeast Asia Monitor: Thailand-Cambodia tensions flare anew. https://www.cfr.org/

Dommen, A. J. (2001). The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Indiana University Press.

Duchâtel, M. (2014). China’s Foreign Policy and the South China Sea. SIPRI Policy Brief.

Economic Intelligence Unit. (2024, July 20). Thailand: Political risks rise as border tensions persist. https://www.eiu.com/

FAZ – Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. (2024, July 24). Grenzkonflikt zwischen Kambodscha und Thailand eskaliert weiter. https://www.faz.net/

Gervaise, N. (2009). The natural and political history of the Kingdom of Siam. White Lotus.

ICG – International Crisis Group. (2021). Thailand: The Evolving Conflict at the Cambodian Border. https://www.crisisgroup.org/

International Court of Justice. (1962). Case concerning the Temple of Preah Vihear (Cambodia v. Thailand). ICJ Reports 1962.

International Court of Justice. (1962, June 15). Temple of Preah Vihear (Cambodia v. Thailand), Merits, Judgment. I.C.J. Reports 1962, p. 6. Retrieved from http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/45/4873.pdf

International Court of Justice. (2013). Interpretation of the Judgment of 15 June 1962 in the Case concerning the Temple of Preah Vihear (Cambodia v. Thailand). ICJ Reports 2013.

Khmer Times. (2025, 24 July). Cambodian artillery hits Thai police post; 8 dead, drones spotted. Khmer Times.

Le Monde Diplomatique. (2024, July 22). Les tensions à la frontière khméro-thaïe, un nouvel échec du multilatéralisme ? https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/

McCargo, D. (2005). The Thaksinization of Thailand. NIAS Press.

Menzel, J. (2022). Völkerrecht und internationale Beziehungen Südostasiens. Nomos Verlag.

Peou, S. (2000). Intervention & Change in Cambodia: Towards Democracy? Palgrave Macmillan.

Phnom Penh Post. (2025, 24 July). Fighting continues along the border between Thailand and Cambodia this morning.

Phnom Penh Post. (2025, 24 July). Thailand opened fire — Cambodia had no choice but to defend itself.

Reuter, T. (Ed.). (2006). Globalization and Identity in Post-Reformasi Indonesia. Routledge.

Reuters. (2024, July 22). Thailand deploys F-16s as Cambodia accuses army of land incursions.

Reuters. (2025, 21 July). Landmine dispute escalates tensions between Thailand, Cambodia.

Reuters. (2025, 23 July). Thailand recalls ambassador to Cambodia amid border tensions.

Reuters. (2025, 24 July). Thai military reports clash with Cambodian troops at border area.

Reuters. (2025, 24 July). Thailand bombs Cambodian targets as border clash escalates.

Reuters. (2025, 24 July). Two soldiers wounded as Thai and Cambodia militaries clash at disputed border.

Richmond, O. P. (2008). Peace in international relations. Routledge.

Roberts, D. W. (2001). Political Transition in Cambodia 1991–99: Power, Elitism and Democracy. Curzon Press.

South China Morning Post. (2024, July 23). Thailand-Cambodia border row: tension rises over disputed farmland.

The BBC. (2011, February 9). Thailand–Cambodia temple dispute. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-12378001

The Daily Telegraph. (2011, March 16). Thailand–Cambodian clashes: timeline. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/cambodia/8308298/Thailand-Cambodian-clashes-timeline.html

The Guardian. (2025, 24 de julio). Thai military closes all Cambodian border checkpoints as death toll from fighting rises.

The Guardian. (2025, 24 July). Thai military closes all Cambodian border checkpoints as death toll from fighting rises. The Nation (Pakistan). (2011, April 30). Thailand, Cambodia clash for 9th day, 16 dead. Retrieved from http://nation.com.pk/pakistan-news-newspaper-daily-english-online/International/30-Apr-2011/Thailand-Cambodia-clash-for-9th-day-16-dead

The Times. (2025, 24 July). Thailand–Cambodia border clashes kill 12 – as it happened.

Thompson, L. C. (2010). Refugee workers in the Indochina exodus, 1975–1982. McFarland & Co.

UNESCO. (2008). World Heritage Committee Adds Preah Vihear Temple to World Heritage List. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/453/

Ungpakorn, J. (2010). Thailand’s crisis and the fight for democracy. White Lotus Press.

UNHCR. (2023). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2022/

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (n.d.). Preah Vihear Temple. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved from http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1224

United Nations. (2024). Security Council Briefing on Regional Tensions in Southeast Asia. https://www.un.org/

World Bank. (2025). Cambodia Economic Update: Maintaining Stability Amid Global Uncertainty. https://www.worldbank.org/

World Bank. (2025). Thailand Economic Monitor: Battling Economic Headwinds. https://www.worldbank.org/