Franz Kafka (1883–1924) stands at the centre of twentieth-century literature as a visionary chronicler of modernity’s anxieties, moral ambiguities, and bureaucratic labyrinths. Yet his fiction, so often framed as prophetic allegory, is inseparable from the intimate dramas that shaped his inner world: strained familial dynamics, ambivalent romantic attachments, professional life in industrial Prague, and the slow, suffocating burden of tuberculosis.

This article refines and expands a biographical-critical examination of Kafka’s life and work, placing particular emphasis on his relationships with Felice Bauer and Grete Bloch, the humiliating “tribunal” of 1914, his retreat to Zürau, the asbestos factory episode, and the creative tensions culminating in The Metamorphosis and The Trial. It argues that Kafka’s literary imagination emerges from a persistent oscillation between acute moral self-scrutiny and the dream of transcendence within systems that obscure or deny it.

Introduction: Kafka in Context

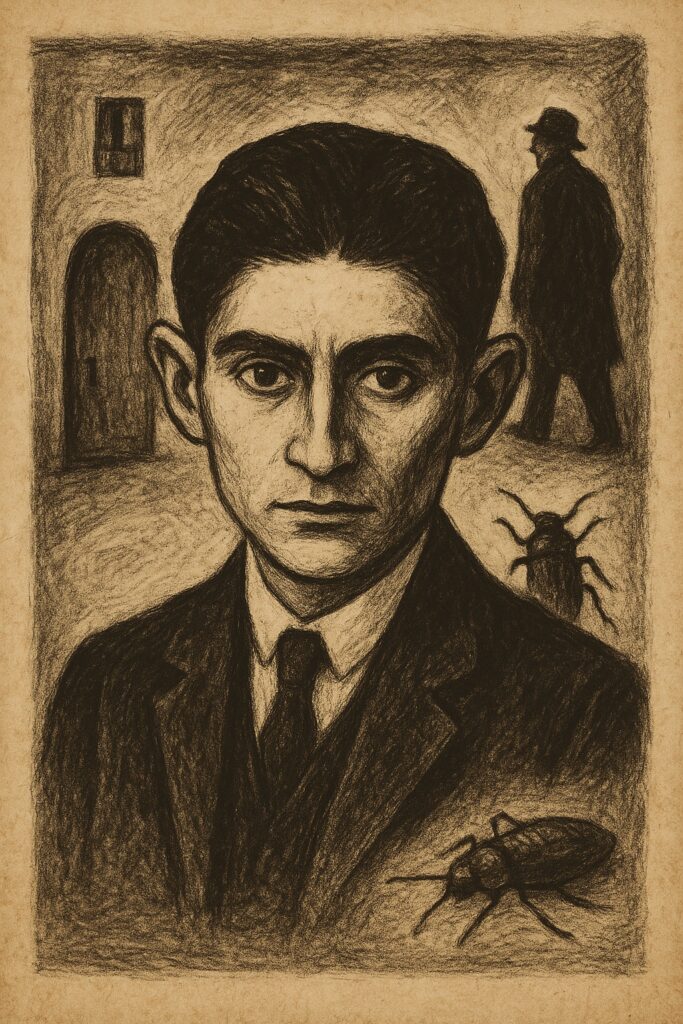

Kafka’s name has become shorthand for the absurd and the oppressive, yet reducing his fiction to metaphysical abstraction risks erasing the deeply personal crises that gave it emotional force. Kafka lived at a cultural, linguistic, and religious crossroads: a German-speaking Jew in Czech-dominated Prague; a dutiful legal bureaucrat who privately cultivated an ascetic devotion to writing; and a man whose most profound commitments—solitude, literature, introspection—collided with social expectations of marriage, productivity, and stability.

His life forms a constellation of contradictions: attachment and withdrawal, ambition and self-erasure, corporeality and spiritual yearning. These tensions were not obstacles to his creativity but its very engine. Kafka’s art is best understood not as escape but as transformation—an alchemical transmutation of personal crisis into symbolic narrative.

Labour, Bureaucracy, and the Asbestos Factory

Kafka’s long tenure at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute profoundly informed his understanding of modern labour. His case reports reveal a meticulous attention to workplace injuries and a deep compassion for the industrial worker’s vulnerability. The bureaucratic precision of his professional life furnished both the content and atmosphere later crystallised in The Trial and The Castle. His involvement in the Hermann & Co. Asbestos Factory, operated by his brother-in-law Karl Hermann, intensified these insights.

The factory—employing primarily young women—exposed Kafka to the dangers of asbestos long before it became a public health issue. His letters show a mixture of business efficiency and ethical discomfort. This dual role—participant in and critic of modern industry—anticipates the divided subjectivity of Josef K. and K., protagonists who inhabit bureaucratic systems that both employ and entrap them.

Felice Bauer, Grete Bloch, and the Intimacies of Anxiety

3.1 Courtship by Correspondence

Kafka’s five-year relationship with Felice Bauer was conducted largely through letters—some of the most revealing documents in twentieth-century literary history. The correspondence oscillates between longing and dread. Kafka repeatedly portrays marriage as a threat to his writing or even a dissolution of the self. The ambivalence is total: he idealises intimacy even as he fears its consequences. Grete Bloch, Felice’s friend, entered this dynamic as mediator and eventually confidante. Her emotional rapport with Kafka, though not romantic, heightened his anxiety and contributed to the eventual catastrophe.

3.2 The 1914 Tribunal

On 12 July 1914, Kafka arrived at Berlin’s Hotel Askanischer Hof expecting reconciliation. Instead, he confronted Felice, her sister Erna, and Grete Bloch, seated formally behind a table. Grete had shown Felice Kafka’s private letters, interpreting them as evidence of duplicity. Kafka later wrote that he stood before them “like a criminal without defence”—a phrase that strikingly prefigures Josef K.’s predicament in The Trial. This “tribunal” shattered the engagement and delivered one of the most traumatic shocks of Kafka’s life. Within weeks, he began drafting The Trial, transforming personal humiliation into a vast allegory of institutionalised guilt.

3.3 The Second Engagement and the Diagnosis

Despite the crisis, Kafka and Felice resumed contact in late 1916 and became briefly re-engaged in July 1917. Weeks later, Kafka suffered his first haemorrhage, signalling the tuberculosis that would define his final years. Marriage seemed impossible. The engagement dissolved quietly, mirroring the narrative pattern in Kafka’s late fiction: aspiration undermined by forces simultaneously external (illness, obligation) and internal (fear, guilt, self-division).

The Metamorphosis: Body, Burden, and Biographical Echoes

Published in 1915, The Metamorphosis remains one of modernity’s most haunting explorations of bodily estrangement. Gregor Samsa’s transformation into a monstrous insect becomes an allegory through which Kafka refracts his deepest anxieties.

4.1 Familial Duty and Economic Burden

Kafka, particularly after his diagnosis, described himself as a burden to his parents. Gregor’s removal from economic usefulness echoes Kafka’s fear of becoming “a parasite” within his home.

4.2 The Body as Cage

Kafka’s letters from this period speak of exhaustion, insomnia, digestive troubles, and a failing body—concerns mirrored in Gregor’s grotesque form. The insect body becomes a metaphor for physical limitation and psychic entrapment.

4.3 Work as Dehumanisation

Gregor’s servitude to a dehumanising employer parallels Kafka’s ambivalent relationship to bureaucratic labour. The irony of Gregor worrying about missing work even after transforming into an insect encapsulates the inversion of priorities imposed by modern capitalism.

4.4 Compassion, Neglect, and the Collapse of Care

The Samsa family’s initial sympathy quickly turns to resentment and neglect. Grete’s shift from caregiver to advocate for Gregor’s removal reveals the fragility of familial compassion under economic stress—an insight Kafka knew intimately. The Metamorphosis thus stands not merely as surreal fantasy but as a symbolic crystallisation of Kafka’s struggles with identity, duty, and corporeality.

Zürau: Illness, Withdrawal, and the Aphoristic Turn

From September 1917 to April 1918, Kafka lived with his sister Ottla in the village of Zürau (Siřem). This retreat, enforced by illness, became a period of profound intellectual productivity. Amid pastoral quiet, Kafka drafted the Zürau Aphorisms: brief, luminous reflections on guilt, time, human limitation, and the possibility of transcendence. One aphorism captures the paradoxical pursuit of meaning in Kafka’s work:

“There is a goal, but no way; what we call the way is hesitation.”

The Zürau period marks a shift from narrative experimentation towards distilled metaphysics—an attempt to articulate a spiritual clarity unavailable within narrative form.

Max Brod and the Afterlife of Kafka

Max Brod’s refusal to burn Kafka’s manuscripts—The Trial, The Castle, Amerika, and countless shorter texts—remains among the most consequential acts of editorial defiance in literary history. Brod shaped early interpretations of Kafka through a spiritual lens, emphasising moral quest and redemptive longing.

The Castle exemplifies Kafka’s late-style architecture of deferral: the protagonist, K., seeks access to an unreachable authority, mirroring Kafka’s own struggles to reconcile desire with obstruction. Its unfinished state amplifies its themes—closure is perpetually withheld.

Amerika, by contrast, presents a more satirical, episodic vision of dislocation. Karl Rossmann’s wanderings through a fantastical United States offer an early exploration of exile, social fragmentation, and the search for belonging. Later critics challenged Brod’s spiritual framework, reading Kafka through existentialism, psychoanalysis, political theory, or deconstruction. Yet without Brod’s decision, Kafka would likely have vanished into archival obscurity. Brod did not merely preserve Kafka; he curated him, ensuring his centrality in modern literary consciousness.

6.1 Comparative Analysis of the Three Unfinished Novels: The Trial, The Castle, and Amerika

Kafka’s three unfinished novels form a loose triad exploring law, authority, and exile—each articulating a distinct narrative atmosphere while sharing structural strategies of interruption and incompletion.

1. Structures of Authority. The Trial presents authority as opaque, decentralised, and self-perpetuating; the Law is everywhere and nowhere, operating through clerks, corridors, and whispered rules. The Castle pushes this logic further: the Castle’s bureaucratic machinery is infinitely remote, its decisions diffused through messengers and intermediaries whose reliability is always in doubt. In Amerika, authority becomes more theatrical and chaotic: instead of a single juridical or bureaucratic power, Karl Rossmann encounters shifting institutions—hotel hierarchies, employment camps, travelling troupes—each promising order but delivering only transience.

2. Protagonists in Displacement. Josef K.’s struggle is legal and existential: he is accused yet uninformed, insisting on innocence he can neither prove nor understand. K., the land surveyor in The Castle, pursues legitimacy rather than absolution, attempting to secure a position he may never have held. Karl Rossmann, however, embodies literal exile: expelled from Europe and adrift in a surreal America, he moves not toward authority but through a sequence of dislocations that destabilise identity itself.

3. Narrative Logic and Unfinishedness. The endings differ in tone despite all being incomplete. The Trial has a known though fragment-included execution scene—Kafka drafted it but left arrangement uncertain. The Castle ends mid-sentence, with K.’s case suspended indefinitely. Amerika concludes with the optimistic but unreal “Nature Theatre of Oklahoma,” offering a utopian promise that critics often read ironically. Each form of incompleteness reflects the novel’s thematic concerns: legal indeterminacy, bureaucratic delay, and the perpetual deferral of belonging.

4. The Function of Space. Space in The Trial is claustrophobic—boarding houses, cramped courts, oppressive offices. The Castle presents a frozen topography of power, in which space itself becomes an instrument of bureaucracy—vast, open, yet structured to deny meaningful entry.

Conclusion

Kafka’s fiction emerges from a life marked by contradiction: longing for love and fear of intimacy, devotion to solitude and the demands of labour, bodily fragility and the aspiration toward transcendence. His crises—romantic, familial, professional, medical—became the raw material of a literature that probes the fault lines of modern existence.

To read Kafka is to enter a world where guilt precedes crime, where institutions dwarf individuals, where bodies betray their owners, and where clarity is forever deferred. Yet his writing also reveals an extraordinary tenderness, ethical sensitivity, and spiritual intensity.

Kafka’s life and work remain inseparable precisely because his stories arise from the consciousness that endured the tensions they depict. For readers navigating the contradictions of modernity—its alienations, uncertainties, and fragile hopes—Kafka continues to illuminate not only the architecture of guilt, but the resilience of those who inhabit it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kafka, F. (1948). The diaries: 1910–1923 (M. Brod, Ed.; J. Kresh, Trans.). Schocken.

Kafka, F. (1973). Letters to Felice (E. Heller & J. Born, Eds.; J. Stern & E. Duckworth, Trans.). Schocken.

Kafka, F. (2006). The Zürau aphorisms (R. Calasso, Ed.; M. Hofmann, Trans.). Harvill Secker.

Kafka, F. (2009). The office writings (S. Corngold, J. Greenberg, & B. Wagner, Eds.). Princeton University Press.

Robertson, R. (2004). Kafka: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Stach, R. (2005). Kafka: The decisive years (S. Frisch, Trans.). Princeton University Press.